POP culture

Thinking about the pop influences that have shaped our understanding of death and dying in Canada.

A death denying culture?

How pop culture influences our understanding of death and dying

contributer TAYLOR BERZINS

I grew up in a home in which my parents replaced my pet goldfish, Cleo, every time it died for five years. They explained to me (many years later) that they allowed Cleo to really die only because I’d noticed him floating upside down. Had I not, who knows how long they would have kept up the rouse to shelter me from my first loss?

Many Canadian kids grow up with the privilege of avoiding exposure to real death, and garner much of their understanding about death and dying through a series of interpretations of things seen on TV, in books or on film.

Learning about and experiencing death without real world context can be traumatizing and certainly impacts the way in which one begins accepting death as a reality of life . To prove my point, here's an example of kids reacting to the ending of the film The Odd Life of Timothy Green:

In the winter, our group sat sipping on lemon ginger teas at aspiring death midwife Emily Jull’s home and discussed the impact of how children learn about death.

“As far as our education process and how people could learn about death and dying, I personally would love to see it be part of the education system the same way sex education is. I would love to see [death] be recognized as something that is natural and something that belongs to each one of us. I would love to see children be able to engage with [death] naturally and at an appropriate stage,” Jull stated.

Jull explained that our children are growing up without having their natural curiosity around death fed, and in turn their curiousity about death is repressed and internalized as fear.

“We treat [sex and death] like these taboos that children can’t handle, like they’re unnatural and we need to repress them, and the fact is, I think we need to do the exact opposite. I think we need to engage and have healthy normal conversations about them and stop making them into these fetished, ridiculous things [sic].”

Michelle Clarke, program co-ordinator for Humber College’s Funeral Studies, also explained to us that she believes that children should be taught about death by their parents.

Clarke explained that she’s alarmed by the amount of parents that would prefer to tell their children that a squashed bug or deceased grandparent is “sleeping” as opposed to “dead.”

“Conversations about death, and dying, and tragedy are commonplace in our home, and I don’t want to shield my kids from it because it could happen to us. So, we have always had a very healthy appreciation, and they have been brought up with this appreciation of death,” explained Clarke.

In an email to professor Charles Wells of Wilfrid Laurier University, who teaches a course about pop culture, we asked whether or not he could discuss the impacts of pop culture on Canadian’s understanding of death and dying. In the email, professor Wells brought up media’s fixation on “undeath.”

Hit television shows like The Walking Dead, Fear the Walking Dead, and Game of Thrones all market an apocalyptic reality in which the dead rise again and in turn imply that death is not a finite process.

Pop culture often reflects a society’s hidden paranoia and insecurities; perhaps the success of television franchises that depend on tropes like zombies reflects our society’s desire to avoid the finality of death?

There is a romantic side to the undead as well. The Twilight franchise casts an laughable lens on the romanticized concept of immortality through the portrayal of hypersexual, sparkly, forever-teenaged vampires. The films Fido, and Warm Bodies presents a reality in which humans find love in with undead zombies and establish romantic bonds that transcend the limitations of mortality. This kind of skirting around finality is dangerous, because unlike the fictions being knit together and oversold by pop media, death is inevitable and death is finite.

Beyond the scope of zombies and vampires, it is important to consider the way in which media portrays a more human kind of dead as well. With shows like Criminal Minds being marathoned by students across the nation, it’s important to understand the inaccuracy in the portrayal of corpses.

In an article for Buzzfeed, “This Is What Goes Into Being A Corpse On ‘NCIS,’” Ariane Lange writes, “NCIS executive producer Mark Horowitz, who casts the dead bodies, said whether he chooses a designated extra, a stuntperson, or an actor is dependent on whether the part requires the character “to appear alive.” If the character is dead for the whole episode, he’ll generally cast an extra. Whether the actor actually plays the corpse during shooting or whether they have to have a dummy made depends on 'how severe their injuries are.'"

Being overexposed to images of studio-manufactured death has skewed our understanding of what real dead bodies look like.

In the 2013 article, “Let’s Remember What Real Dead Bodies Look Like,” Caitlin Doughty writes, “Popular culture images of death fall on the extreme edges of the spectrum: either the prettied-up dead (that is to say, OBVIOUSLY living actors in TV crime shows) or the grotesque horror living-dead types.”

There is an oversaturation of marginalized people being killed or dying in pop culture as well.

In the article “‘Anyone Can Die?’ TV’s Recent Death Toll Says Otherwise,” Maureen Ryan explains that women, people of colour and LGBTQ characters are killed off of popular TV franchises at an extremely disproportionate rate than that of their white male counterparts.

“Those of us who continually promote the inclusion of a wider, more diverse array of TV creators bang that drum for a lot of reasons. One of them is the avoidance of preventable events, like this spring’s Festival of Tired Tropes, which managed to invoke standbys like Bury Your Gays, Women in Refrigerators and the Black Guy Always Dies.”

It’s not just TV. A blog from 1999 called Women in Refrigerators tracked the violent deaths of female comic book heroines. The title of the blog mocks a trope in comic books in which dead female characters are often stuffed into fridges. The comprehensive list can be found here: http://lby3.com/wir/women.html

By systemically normalizing the violent and meaningless deaths of marginalized people in pop culture, we’ve skewed our understanding of death and dying as a society.

“I think too, and I don’t know, I would love to see formal research on the link between children being quote on quote protected from death and their obsessive fascination with videogames that cause death,” said Clarke.

“Like, my little guy, my oldest is just now getting into videogames, but he’s only six, so he’s not obviously into a whole lot of stuff, but there are some videogames that he plays with my husband where you kill the other guy and there was one that wasn’t graphic, but it bothered him, and he’s like ‘I don’t want to play that.’ He understands it, right, and it’s not on a level that we understand, but he gets it, that this isn’t okay. Like he gets upset when other kids kill bugs because he understands that that shouldn’t happen. And so, it makes me think, has our society gone so far into a death denying existence that it’s alright to kill something and it’s okay to be cruel to something and let it suffer because we just don’t understand what that really means and what the implications are of it.”

Are YOU obsessed with death?

The Kijiji Experience

contributer JACLYN BROWN

Ithink it was TLC’s show Weird Obsessions that sparked my original idea to seek out Brantford’s death obsessed. I was flipping channels with a bowl of popcorn when I came across some old lady who spent her entire day pacing the rows of cemeteries. In her spare time she would try out coffins to see which one was the most comfortable, request funeral homes tours and even shop for the perfect cemetery plot. I was totally enthralled with this woman, out of all the things in the world to be interested in she chose death, but why? As I embarked on a year-long study of death, images from the show echoed in my mind. I thought to myself there must be others like her. I was curious if her death obsession stemmed from fear or curiosity, as she quoted the death of her mother as the starting point of her obsession.

So I went where any journalist would go to extract the oddities of society – Kijiji.

There is some elusive quality about the Internet that inherently attracts humanity’s most unique characters. I thought it would be interesting to interview someone whose life has been taken over by death, either in a positive or negative way. Either way, I figured someone would respond. It was the perfect platform to lure in unusual views of death. I posted the ad in early October in hopes we could gage how popular culture has helped or hindered the death perceptions of people. The ad read:

Are you obsessed with death? We want to talk to you! We are three journalism students from Wilfrid Laurier University working on a yearlong project about death perceptions in Canada. We are currently seeking individuals who consider themselves obsessed or highly interested in death for an on-camera interview. If you feel you can contribute to our project please contact us explaining your story or interest in death. We look forward to hearing from you and are happy to answer any questions.

It was dripping with promise. What death-crazed person could pass up an opportunity to gush about their obsession to an open eared journalist? I was a little nervous to say the least with memories of Craig’s list-gone-wrong stories milling in my mind. “What if you meet up with them and they’re so in love with death they kill you?” Muttered my roommate. Luckily my skin and hopes were thicker than her piercing words, as I was determined to find an interviewee brimming with an all-encompassing passion for death. Also, I’m happy to report I’m alive and well.

My confidence could be partly attributed to the reoccurring theme of western culture as death denying. I didn’t need to enroll in a university research project to come to this conclusion because you see it everywhere. You feel the awkward tension rise if someone brings up death in a conversation. The invisible conversation about death in Canadian culture insinuates the purest form of fear. If we are terrified of merely discussing our demise, this surely has the potential to drive some of us mad. The meaning of life has stumped us for years and if we don’t have an established and integrated outlet to discuss the fears around our fate, we are left to our own devices. Death is as natural as life itself but I was sure this suppressed conversation would mean a bite on the Kijiji fishing line.

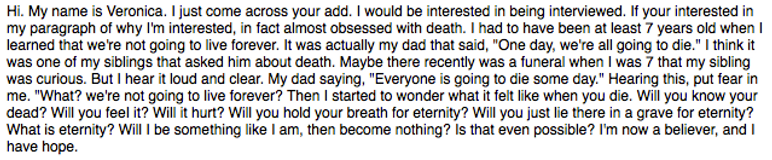

Low and behold emails started to crawl into my inbox. There were about five really weird emails where people would just send bizarre comments about death or even send me odd inspiring quotes or photos (which is completely expected when it comes to Kijiji) Here was the first response I received:

What I love about the response from Veronica is how she articulates all the insecurities and questions we all have about death. It seems like her father may have unintentionally got the ball rolling in the direction of fearing death. Her quick fire questions embody the panic we all feel when we realize, for the first time, we’re all going to die. This clearly illustrates a hole in society since there is no widespread organized way for us to talk about death. As I was reading her response, I couldn’t help but think about the education system. What if the school system started integrating courses about death into the curriculum? This is a wholly idealist pitch, but it’s so clear from Veronica and society that we’ve never been formally taught about what happens when we die. Perhaps the age to start the conversation would be around 10 when you become conscious of mortality. She notes at the end she has hope now, but unfortunately once we set a date for the interview she told me she changed her mind. Got to love Kijiji.

I received a second response a few days later from a user named Sammy:

“The more I learned, the less I was afraid.”

I love this sentence. Sammy unknowingly articulated the most effortless embodiment of how we can start to change death perceptions, through learning. She found her niche of understanding within meditation and acknowledgment of her soul. She learned about death, eradicated her personal fear, and feels free because of it. Isn’t that amazing? We have the key to freeing ourselves from fearing death through education. It’s hard to speculate a starting point to integrate the death conversation into daily life because we’ve burrowed ourselves so deep into death-fear we don’t want to talk about it. Throughout our research we’ve heard of a movement called Death Cafes. Basically it’s a safe space for people to gather and talk about everything death, but it’s not a grief support group. It’s a simple circle for talking about death in an attempt to turn our culture from death denying to death accepting. We are currently scoping Death Cafes in the area to see its making any changes in people’s perceptions. There is no denying this movement will really be key to mobilizing death conversation.

Now, I know you’re probably dying (no pun intended) to see the interview with these death gurus. However, another elusive quality about kijiji is that if your change your mind- it’s very easy to ignore the original poster. After several valiant emails attempting to book an interview, the repliers got cold feet. I wouldn’t write this experience off as completely fruitless because I think it was a really good place to start. These two responses beautifully articulated insecurities and even coping mechanisms regarding dying. Their answers reveal the impact of popular culture’s silent death conversation. It also suggests how the lack of cohesive cultural understanding has left us to navigate death with our own devices. If we all share the fear then we could all share the conversation surrounding this fear. It’s becoming increasingly clear that talking about death is the easiest way to feel at ease about our own mortality.